Key Crew

Writer/Director – Jason Neulander

Lead Producer – Thomas Fernandes

Producer – Jennifer Kuczaj

Cinematographer – Christina Voros

Editor – Mike Saenz

Composer – Graham Reynolds

Attached Cast

Harwick – Tim Blake Nelson

Logline

Ten years after the Civil War, Helen is taken from her home by a band of Comanches. Her father organizes a posse to find her, but he’s keeping a terrible secret and nothing goes as planned.

Synopsis

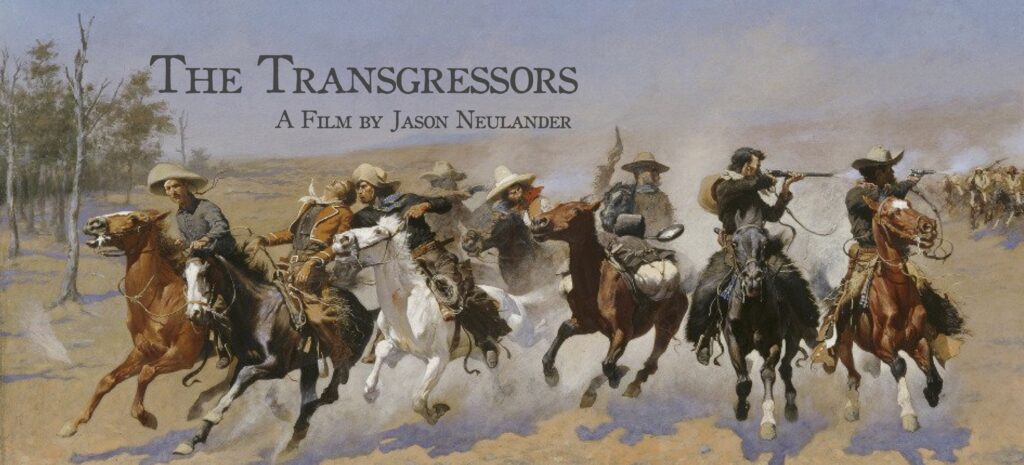

The Transgressors is a character-driven thriller that juxtaposes the timeless and epic legend The Iliad with the myth of the American West. It features an ensemble cast in which there are no clear heroes, exploring these characters’ relationships to each other and their instincts for action and violence within the framework of the pervasive racism in Texas in the late 19th Century.

North Texas, 1875. Church Shipman and Josiah Harwick, two early settlers of the territory, hire a posse to find and ransom Church’s daughter Helen, who has been taken by Red Hawk and his band of Comanches. The posse consists of three battle-hardened Civil War veterans, Zach Wilbarger, Lariat Westall, and the Comanche scout Wolf Paw, each haunted by his own experience in the war; four green young men, Will Carter, Noah Greeley, Bill Thorp, and Lariat’s younger brother Peter, who dream of becoming heroes; and Barnaby Ness, a former slave of Shipman’s who is in it purely for the money.

Harwick wants to avoid bloodshed, but the mission quickly begins to unravel as the men track the Comanches to the Palo Duro Canyon. First, Wilbarger murders a Lipan Apache warrior in cold blood. Then, the group stumbles across Cassie, a traumatized escapee from what might be Red Hawk’s band. Once in the canyon, though, the men start to get picked off and in their paranoia they turn on themselves. Then Harwick discovers a horrible truth about Shipman and Helen. By the time Cassie reveals she knows what Helen’s father “did to her” it’s too late to turn back. The only path forward is unspeakable violence.

Yet there is hope, if not for these characters, then maybe for their descendants. In the final moments of the film, Helen and Red Hawk dream of a future that can’t be theirs, but still might one day come to pass.

Artist statement

Towards the end of The Iliad, Priam, the proud king of Troy, sneaks into Achilles’ tent. He comes not to murder the man who killed his son Hector, but rather to beg for the remains so he can perform the funeral rituals that will send his son’s soul safely to the underworld. He gives an impassioned plea that equates his relationship with his son to Achilles’ relationship with his own father, defusing Achilles’ rage and ultimately heading home with his son’s body.

When I first read it, this scene made me cry. The ancient Greeks believed that anyone who wasn’t Greek was a barbarian. Yet in this scene, the “enemy”, the “alien”, the “other” turns out to be much like us — unabashedly and empathetically human. How astounding, I thought, that this story written thousands of years ago and sung ages before that still resonates so powerfully in our own time of deep tribalism. I knew immediately I needed to find a way to share this ancient snapshot of humanity with today’s audiences. With The Transgressors, I’ve taken key elements, characters, and themes from this timeless myth and juxtaposed them with one of our own essential cultural myths, that of the American West. The Greeks become the posse and the Trojans, the Comanches.

The Transgressors is a complex and epic adventure that explores the nature of mythology — who writes it, how it shapes our identity, and how the hegemony appropriates it — to tell a story about how those in power have narrated the lives of those on the margins, often erasing those voices to tragic ends. I think not only of the Trail of Tears and the Jim Crow South, but also contemporary events like the Kavanaugh hearings, police shootings of unarmed black men, ICE arrests, the Syrian refugee crisis, and Muslim internment camps in China. As the onion of the story in The Transgressors is unpeeled, we discover that what seemed like obvious truths (Helen is kidnapped, the kidnappers are nothing but savages, a band of heroes attempts her rescue) turn out to be false and that these “alternative facts” lead only to tragedy.

In addition to myth, I extensively researched the history of Texas just after the Civil War. One key source was the book Indian Depredations in Texas, a racist first-hand account of those times published in the 1890s. I became fascinated by how the myth of white supremacy informed the author’s interpretation of actual events. Like the author of Depredations, the film’s posse see their circumstances only through the filter of their prejudices, which they are incapable of recognizing until it’s too late.

But the story I’m telling isn’t simply “white man bad/minorities and women good.” The middle of the 19th century was a volatile period in Texas. I spent months researching this history and became particularly fascinated by the complex relationship between the Comanches and the Anglo settlers. My research led me unexpectedly to the conclusion that while the Anglos were definitely not in the right in their treatment of the Comanche people, the Comanches were also brutal towards the settlers. In fact, they were brutal to everyone including the other Native American tribes living in the area before the settlers arrived. The Comanches were a proud warrior culture and part of that culture was to engage in battle with any other culture who crossed their path. The settlers had good reason to be terrified of them. The brutalities shown and discussed in my screenplay are all taken from actual events. In other words, the history of that time is much more nuanced than I thought it was going into the project. That nuance is an essential variable in the film itself.

Thus, within the ensemble cast, even the worst characters have understandable motivations, tightening the knot as the story moves forward (all the way to the last shot). At first, The Transgressors seems like a “traditional Western” with a few hints that it won’t be (eg. Shipman lies about how his house burned down; the inherent racism of many of the characters), but then it becomes something different, closer to Cormack McCarthy than Larry McMurtry. My goal is to lull the audience into a comfort zone to then shatter their expectations, while still building a story that sweeps us away towards its inevitable conclusion.

From hope to horror: the look and feel of The Transgressors

I’m inspired not only by John Ford’s The Searchers and Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, but also by the cinematography of Freddie Young (Lawrence of Arabia) and Vittorio Storano (Apocalypse Now), DPs who understood how essential landscape can be to storytelling. The changing landscape of our storyline is itself a character in the production.

The shoot is timed to take advantage of Texas’ legendary wildflower season, during which splashes of pastel color bleed through the yellow of the grassland. As the film moves towards its violent end, the landscape changes from those pastels (representing hope) to the otherworldly red dirt and spiked flora of the Palo Duro canyon (representing horror).

The film will be shot in widescreen format, reminiscent of the epics of the late-50s/early-60s. Throughout, the camera will shoot from below the actors’ faces, making them appear mythical on screen. When the film begins, the look will echo classics like Lawrence of Arabia, but as the story devolves into chaos, the camerawork will adapt, ending in a documentary style that puts the viewer in the middle of the action.

Christina Voros is attached as our cinematographer. She is ideal for this project. Her work ranges from feature documentaries to directing and shooting episodes of the NBC/Paramount Western Yellowstone with Kevin Costner. Her work embodies the full range of the look and feel of The Transgressors — and she’s delightful to work with.

Comments are closed.